Monthly Calendar-Report for June 2015

All because my May Calendar-Report had 149 readers (and counting), a record.

Come-on, guys, it’s only a blog. I get 10-20 readers on average, and most are from links I send e-mail.

And in my humble opinion, my Calendar-Reports are the most boring thing I write.

“Someone must have ‘shared’ it,” my brother said.)

Eastbound stacker charges Brickyard Crossing on Track One. (Photo by Jack Hughes.)

—When I first looked at the photo my brother took at Brickyard Crossing, I decided it was one I could never take, that it was too close to the tracks.

The picture is the June 2015 entry of my own calendar.

It’s not actually Brickyard Road. It’s Porta Road, the only grade-crossing in Altoona. It has little traffic.

The line is so busy Altoona and other towns built bridges under and over the tracks.

There used to be a brickyard adjacent, so the railroad and fans call it “Brickyard.”

But where my brother took this picture is not unsafe. He’s up against an equipment-box about 10 feet from the tracks.

It’s just that an approaching train looks imposing.

He showed me the area recently. I decided I could do that.

10 feet is as close as I wanna get.

The train is a stacker, double-stacked freight containers in wellcars designed for double-stacks.

Often the wellcars are three or five hooked together with drawbars, and they share a single truck at each end.

Sometimes you see empty wellcars going back for more containers. That’s called a “bare-table” train.

The stacker begins and ends at a depot that can load and unload containers.

Containers often come in ships from overseas, but they are 40 feet, so-called “international containers.” Containers can go up to 53 feet, the standard trailer-length. “Domestic containers.” Most wellcars can secure either length.

Southern Pacific was the first railroad to use double-stacks, and quickly all railroads were doing it, or at least wanted to. —Southern Pacific is no more; it was merged into Union Pacific.

Double-stacked containers require more overhead clearance than many eastern railroads had, like this Pennsylvania Railroad main.

Tunnels had to be enlarged to clear double-stacks, bridges raised, or tracks lowered.

On the CSX line in western Rochester is a footbridge. You can see it. The tracks dip so the bridge will clear double-stacks.

Not long ago the original Pennsy tunnels through Allegheny summit could not clear double-stacks, which put PA at a commercial disadvantage.

At that time the line was Conrail, so two tunnels were enlarged with state aid. A third tunnel was abandoned, and Pennsy’s original Allegheny tunnel made wide enough for two tracks.

The locomotive is a General-Electric Dash 9-44CW, 4,400 horsepower. I see three units. The engines at right are a helper-set, two SD40-Es.

The stackers don’t always get helpers, but they do if they’re long and heavy. A stacker can usually climb The Hill unassisted. There are no helpers on the front of this train.

Truckers are upset with stackers. But imagine 200 or more trucks clogging an interstate. That’s also 200 or more drivers.

A single double-stack can move 200 or more containers with only a crew of two or three.

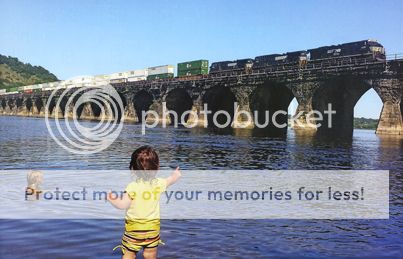

Mighty Rockville. (Photo by Daniel Juhasz.)

—None of my calendar-photos are extraordinary, but the best is the one above, Pennsy’s Rockville Bridge.

It’s the June 2015 entry of my Norfolk Southern Employees’ Photography-Contest calendar.

Rockville is where the Pennsylvania Railroad crossed one of the main impediments to commerce across PA, the wide Susquehanna (“suss-kwee-HA-nuh”) River, but very shallow.

It’s not deep enough to pass ocean-going ships. About all it can accommodate is small watercraft without much draft.

Rockville Bridge is one of the signature engineering achievements of Mighty Pennsy, as much as Horseshoe Curve.

At least this third bridge, finished in 1902.

It was built wide enough for four tracks — 52 feet. It’s not four tracks now, but was for a long time.

Pennsy, of course, is no more. The line is owned and operated by Norfolk Southern, a 1982 merger of Norfolk & Western and Southern Railway.

Pennsy, once the largest railroad in the world, was affected by all the things that brought down east-coast railroading, expensive commuter operations, taxes, and airline competition and the Eisenhower Interstate System.

Pennsy had to merge with arch-rival New York Central, the other heavy-hitter to the east coast.

That was Penn-Central, which went bankrupt in two years — the largest bankruptcy ever at that time.

Penn-Central was followed by Conrail, at first a government attempt to rationalize east-coast railroad service. Other railroads were also going bankrupt.

Conrail became successful and eventually privatized.

Conrail was broken up and sold in 1999. CSX got the old New York Central main across New York, and Norfolk Southern got the old ex-Pennsy main across PA.

The train pictured will probably go down to Harrisburg where it will switch over to the old Reading (“REDD-ing;” not “READ-ing”) main toward the New York City Area.

The line becomes ex-Jersey Central, and doesn’t actually access New York City. The containers will get unloaded in north Jersey, then trucked into New York City.

The old Pennsy line to New York City is now part of Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor. The old Pennsy electrified line between Philadelphia and Harrisburg is also Amtrak.

I used to say it would take a direct hit from a thermonuclear warhead to take out Rockville Bridge.

It’s concrete with stone facing, although I’m getting discussion about whether it’s all stone masonry.

But a small part washed out not long ago.

The Susquehanna can flood; it drains a very large area.

No matter. Rockville is impressive. 48 70-foot arches marching across the river; 3,820 feet, incredibly long.

And it was built for four parallel tracks.

1969 Douglass-Yenko Super Camaro. (Photo by Peter Harholdt©.)

—The June 2015 entry in my Motorbooks Musclecar calendar is a 1969 Douglass-Yenko Super Camaro.

The Douglass-Yenko Super Camaro is a special car. Any Yenko Camaro is rare, and special.

But the Douglass-Yenko Super Camaro is one Yenko let dealer Jack Douglass build under license. It has the COPO 9561 L-72 427 cubic-inch high-performance motor. It also has the Endura bumper and a COPO 9737 sportscar conversion package. (COPO 9737 consisted of E70X15 tires on Rally Wheels, a 140 mph speedometer, and a 1-inch front stabilizer bar.)

People love the ’69 Camaro, but I think the ’70 Z-28 is one of the best-looking cars ever.

|

| A ’70 Z-28 Camaro. |

|

| Pontiac’s Firebird. (Photo by Peter Harholdt©.) |

Not too long ago I saw a ’69 Camaro with updates to its motor and suspension. They made it as good as the current Camaro.

Okay, but it was still a ’69 Camaro.

Every once-in-a -while I get the Camaro bug.

But it’s not the ’69.

I prefer the earlier Camaros, the ’67 or ’68, on which the ’69 is based. The sheetmetal is slightly different, but the top is the same. It’s pretty much the same as the earlier Camaro, and that’s a small Detroit sedan.

Not until the 1970 model-year did Chevrolet make big changes to the Camaro. And when they did they made it a great-looking car, although it was still a small Detroit sedan underneath.

Not your normal M-1. (Photo by Don Wood©.)

—The June 2015 entry of my Audio-Visual Designs black-and-white All-Pennsy Calendar is a photograph by Don Wood, the guy whose pictures graced the first Audio-Visual Designs All-Pennsy Calendars. Photographing Pennsy as steam-usage was coming to a close, he particularly gravitated toward Pennsy’s 4-8-2 Mountain engine, the best steam-locomotive Pennsy ever had.

Mountains were often assigned to the Middle Division, Harrisburg to Altoona. It’s an uphill climb, but not much. A Mountain could hold 40-50 mph.

This photograph is not one of Wood’s better photographs. It’s included because of the locomotive’s fittings.

Usually when a locomotive received the front-end “beauty treatment” of relocating the headlight atop the smokebox, and bringing the generator down on the smokebox front, along with a platform to work on it, the locomotive also received a massive cast-steel pilot.

This engine still has its original slatted pilot.

|

| A recent slab-train (empty). (Photo by BobbaLew.) |

A Yakovlev Yak-3M. (Photo by Philip Makanna©.)

—The June 2015 entry of my Ghosts WWII warbirds calendar is an airplane I’m not familiar with.

It’s a Yakovlev Yak-3M, a Russian fighter-plane. Pretty much along the lines of the Curtiss P-40, the Supermarine Spitfire, and the Messerschmidt, a water-cooled V12 motor pulling a single-seat monoplane (one wing).

I’ll let my WWII warbirds site weigh in:

“The first attempt to build a fighter called the Yak-3 was shelved in 1941 due to a lack of building materials and an unreliable engine. The second attempt used the Yak-1M, already in production, to maintain the high number of planes being built.

The Yak-3 had a new, smaller wing and smaller dimensions then its predecessor. Its light weight gave the Yak-3 more agility. The Yak-3 completed trials in October of 1943 and began combat in July of 1944.

In August, small numbers of Yak-3s were built with an improved engine generating 1,700 horsepower, and the aircraft saw limited combat action in 1945.

During the final two years of the WWII, the Yak-3 proved itself a powerful dogfighter. Tough and agile below an altitude of 13,000 feet, the Yak-3 dominated the skies over the battlefields of the Eastern Front during the closing years of the war.”

It seems every major power had to have a version of the WWII fighter-plane; for example, the Brits the Spitfire, the Yanks the Mustang, and the Russkies this Yakovlev Yak-3M.

The Mustang was the best of the lot — although it had the advantage of being designed later.

Apparently the Yak-3M was pretty good, good enough for flyers to have Yakovlev build examples long after the war.

The newer Yak-3Ms are powered by Allison V12s, the engines that powered the P-38 Lightning and the P-40.

Only five of the newer Yak-3Ms are left. All the WWII Yak-3Ms are gone.

Too bad the P-51 Mustang can’t be remanufactured like the newer Yak-3Ms, although by now the restorers are probably building P-51 components new.

Even old the P-51 is a fabulous airplane.

Not the first time. (Photo by Robert Olmsted.)

Not the first time. (Photo by Robert Olmsted.)—The June 2015 entry in my All-Pennsy color calendar is three EMD E-units powering Pennsy’s Manhattan Limited out of Chicago.

This photograph has run before in this calendar, I think twice.

I’m stealing the picture from an earlier Calendar-Report, June of 2014.

That’s exactly one year ago. You’d think the calendar publishers would avoid previously published art.

Despite that, it’s a pretty good picture, and I guess I can look at it again.

The Es will come off in Harrisburg, replaced by a single GG-1.

Pennsy considered electrifying its railroad in PA — that is, Harrisburg to Pittsburgh — but never did.

I wonder if it would have lasted if it had been electrified; much of Pennsy’s electrification has been taken down.

Philadelphia-to-Harrisburg is still electrified, although it’s Amtrak.

Would the across-PA line have become Amtrak if the line had been electrified? There is no semi-parallel railroad route Harrisburg to Pittsburgh. From Harrisburg to the New York City area is the old Reading route, which is Norfolk Southern’s (previously Conrail’s) access to the New York City area.

The old Pennsy line to New York is now Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor.

Who knows what would have happened if the old Pennsy line to Pittsburgh had become Amtrak.

Only one cross-PA passenger-train runs on it, actually two per day, Amtrak’s Pennsylvanian, one in each direction.

If it had been electrified the wire probably would have come down. Electrification is high maintenance.

A railfan friend poo-poos “What ifs.” He’s a fan of New York, Chicago & St. Louis (Nickel Plate).

Nickel Plate never attained New York City, only Buffalo. But if it had merged the old West Shore it could have.

The West Shore was an effort by Pennsy to offset the power of New York Central, but was merged into New York Central to get NYC to stop investing in the South Pennsylvania Railroad, graded but never finished. South Pennsylvania Railroad crossed PA, and was intended to compete with Pennsy, which Andrew Carnegie was mad at because he thought Pennsy was charging too much.

The merger of West Shore into NYC was instigated by J.P. Morgan to stop the infighting.

But West Shore could have been Nickel Plate’s access to the New York City area. Nickel Plate was competition for New York Central. It pretty much parallels NYC, especially along Lake Erie to Buffalo.

Nickel Plate was eventually merged into Norfolk & Western, which became part of Norfolk Southern. Norfolk Southern now owns the old Erie mainline from Buffalo across southern New York.

So now NS is doing what Nickel Plate could have done; accessing the New York City area via the old Nickel Plate and the old Erie.

Well, at least it’s a Flatty. (Photo by Scott Williamson.)

—June 2015 entry in my Oxman Hotrod Calendar is a radically-altered 1934 Ford pickup. The front axle was moved seven inches forward, and the cab moved back three inches. The pickup-bed is hand-made.

Everything looks to be chopped and sectioned and channeled and lowered; begging the question how does one sit in such a thing? You’re probably sitting on the floor, scrunched under that top-chop.

Yrs Trly has never thought much of pickup hotrods, I suppose because they ain’t much of a pickup. About all you could carry is a bag of ice, or an 80-pound sack of concrete-mix.

You couldn’t carry a load of manure.

Well, it looks nice with all those chassis mods, but I wonder how it handles.

This ain’t what Old Henry marketed, not with the front-axle up where it is.

And the body is bare metal. What if it rains? Rust galore!

|

| Offy heads. (Photo by BobbaLew.) |

A friend, since deceased, had a 1949 Ford hotrod with FlatHead V8.

The car looked nice, but we used to say the motor was worth more than the car.

FlatHead V8s, the foundation of hot-rodding, are becoming rare. And his car had the ultra-rare Offenhauser (“OFF-en-houze-er”) aluminum cylinder-head castings. Higher compression and finned.

He drove it out to my house once, since I have a pit, and it needed steering work.

At least it made it, but it spit coolant, etc all over the road.

The pollution-police would have gone ballistic, but Old Henry wouldn’t have cared.

I sat in it once and was scared. The steering-column was waiting to impale my chest, and the unpadded dash was waiting for my face. Seat-belts, are you kidding?

Fuzzy-dice were on the interior rear-view mirror, and the standard three-speed tranny was floor-shifted.

In its day the car was probably good for 100 mph. I feel much safer in current cars, and belted in.

Add a scrunched seating-position to all that, and you get the car pictured; just about undriveable.

With that bare-metal body it’s probably a trailer-queen. You dare not get it wet.

Another 4-4-2 Olds.

—The June entry of my Jim LePore Musclecar calendar is a 1967 Oldsmobile 4-4-2; four-barrel carburetor, four-speed transmission, dual exhausts.

Jim LePore (“luh-POOR”) is a widower like me, and also a car-guy.

He bought a white 2010 Camaro SS, and named it after his late wife.

He drives it little, mainly to car-shows, where he shows it.

He’s a hair older than me.

True-to-form, the 4-4-2 is a GM product, due to the calendar being published by Farnsworth of Canandaigua.

Farnsworth is a car-dealer for GM cars, Chevrolets and Cadillacs.

And Randall Buick and GMC (Randall Farnsworth is the guy’s name).

The calendar purports to be a musclecar calendar, but it’s only GM cars.

Which is okay to my humble mind. The best musclecars were made by General Motors. Fords lost their tune quickly, and Chrysler musclecars were big.

Car and Driver magazine always claimed the 4-4-2 handled better than other musclecars. Who knows how reliable that was, since their business was selling ads.

I also think the 4-4-2 was the best-looking musclecar, but they’re big. A 396 Chevelle passed my house a while ago, and I couldn’t help noticing how long its trunk was.

Musclecars also don’t handle very well. The rear-axle was cheaply suspended, and could twist due to engine-torque.

The front-suspension is A-arm, whereas now MacPherson struts are used — and handle better.

The car also uses uses a solid rear-axle with heavy integral differential, that can hop in a turn.

Even Mustang has come to independent rear-suspension. The solid rear axle can be made to handle quite well, but that’s NASCAR.

I also think the 4-4-2 featured in last month’s LePore Musclecar calendar, a 1971, looked better than this 1967.

Whatever, I hear any 4-4-2 was a blast to drive. Lotta motor. Floor it and hang on for dear life!

Labels: Monthly Calendar Report

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home