Monthly Calendar-Report for March 2015

Eastbound Y94 into Slope Interlocking. (Photo by BobbaLew.)

—The March 2015 entry of my own calendar is a potshot.

It’s eastbound Y94 entering Slope Interlocking under 24th St. overpass in Altoona (PA).

Slope Interlocking is where trains enter the vast Altoona yard complex. It’s also where the uphill grade over Allegheny Mountain begins. There used to be a tower.

This picture was taken January 12th, 2013, when my brother-from-northern-DE and his son were helping me chase trains.

My brother is not a railfan, but my nephew is.

Phil Faudi (“FOW-dee;” as in “wow”), the railfan extraordinaire from Altoona who has helped me chase trains in the area, was not with us. His wife has Multiple Sclerosis, and he’s afraid of her falling. So he stays at home. What he does is monitor his railroad-radio scanner, and call my cellphone.

We had gone to 24th St. overpass hoping to photograph train 04T, Amtrak’s eastbound Pennsylvanian. The Pennsylvanian is state-sponsored, and is the only passenger-train left on this storied line, which used to host many passenger-trains.

|

| 04T, the eastbound Pennsylvanian. (Photo by Tom Hughes.) |

Other trains passed under us, climbing the mountain, or descending.

Y94 has a helper-set up front. If it’s 6300-series it’s an SD40-E helper locomotive.

A helper-set is two SD40-Es used only in helper-service over the mountain.

SD40-Es are SD-50s downrated by the railroad to 3,000 horsepower. SD-50s were 3,500 horsepower.

Helpers get added or detached in Altoona, and at locations west of The Hill. They help the train up The Hill, and also add braking to a train descending. A westbound helper-set may run all the way to Pittsburgh, and that’s helping hold back the train once over The Hill.

The train is following the old Pennsylvania Railroad, the same alignment laid out in 1854. It was, and still is, an engineering marvel, that an operable railroad could be built over Allegheny Mountain, once a barrier to commerce.

Helpers were needed, but the line is not insanely difficult.

The grade west is 1.75%; that’s 1.75 feet up for every 100 feet forward. Go above 2% and you’re asking for trouble. Above 4% is just about impossible. Any steeper and the locomotive driving-wheels, especially side-rod steam-locomotives, won’t hold the rail.

The hitch to Allegheny Mountain, and the railroad thereon, is how heavy a train can be operated. The grade drags a train climbing, and trains try to run away descending.

So here came Y94 down The Hill, eastbound on Track One. I shot some photos of the train up the track, but then at the last second I hung my camera over the bridge-rail and snagged this potshot.

Often my potshots are my best photographs.

The winner of the Battle of Britain, not the Spitfire. (Photo by Philip Makanna©.)

—The March 2015 entry of my Ghosts WWII warbirds calendar is a Hawker Hurricane, many of which defended Great Britain against Nazi air-raids.

|

| Spitfire! |

Often the Spitfire is credited with turning back Hitler’s Luftwaffe.

But it was more the Hurricane.

Hitler would send his twin-engine dive-bombers, and Hurricanes would shoot them out of the air.

I’ll let my WWII warbirds site weigh in:

“In 1933, Hawker’s chief designer, Sydney Camm, decided to design an aircraft which would fulfill a British Air Ministry specification calling for a new monoplane fighter.

His prototype, powered by a 990 horsepower Rolls Royce Merlin ‘C’ engine, first flew on November 6th, 1935, and quickly surpassed expectations and performance estimates.

Official trials began three months later, and in June of 1936, Hawker received an initial order for 600 aircraft from the Royal Air Force.

The first aircraft had fabric wings. To power the new aircraft (now officially designated the ‘Hurricane,’) the RAF ordered the new 1,030 horsepower Merlin II engine.

The first production Hurricane flew on October 12th, 1937, and was delivered to the 111 Squadron at RAF Northolt two months later.

A year later, around 200 had been delivered, and demand for the airplane had increased enough that Hawker contracted with the Gloster Aircraft company to build them also.

During the production run, the fabric-covered wing was replaced by an all-metal one, a bullet-proof windscreen was added, and the engine was upgraded to the Merlin III.

August 1940 brought what has become the Hurricane’s shining moment in history: The Battle of Britain. RAF Hurricanes accounted for more enemy aircraft kills than all other defenses combined, including all aircraft and ground defenses.”

I’m told the Hurricane has a fabric-covered empennage; the rudder and horizontal stabilizer. Even part of the fuselage is fabric-covered, a very old way of doing things.

The fact it was fabric-covered meant it could be shot up and still be flyable. Bullets could pass right through.

The Hurricane has the water-cooled Rolls-Royce Merlin V12 engine, but not the same motor as the Spitfire. The Spitfire is 1,478 horsepower; a Hurricane is 1,280 horsepower.

In the heart of the system. (Photo by Mark Erickson.)

—The March 2015 entry of my Norfolk Southern Employees’ Photography-Contest calendar is the heart of the old Norfolk & Western railroad, Roanoke.

Norfolk Southern is the merger of Norfolk & Western and Southern Railway in 1982.

Norfolk & Western was mainly a coal-carrier; it carted coal from Pocahontas Coalfield in western Virginia and West Virginia.

Norfolk & Western carried so much coal it became immensely successful. The coal seams — Pocahontas No. 3, No. 4, No. 6, and No. 11 — are some of the best coal in the world, and are rated at 15,000 Btu/lb.

Norfolk & Western, a combination of various railroads in the area, ended up carrying coal for all over the world.

Years ago mighty Pennsylvania Railroad wanted to merge with Norfolk & Western since PRR was a PA coal-carrier.

That wasn’t allowed, but now Norfolk Southern owns and operates the original Pennsylvania Railroad across PA. It also owns what used to be Monongahela Railroad, which taps a huge coal-mine in southwestern PA.

Norfolk & Western transloaded coal to ocean-going ships at Lambert’s Point, VA. That’s now Norfolk Southern.

True to the cargo it carried, N&W became the last mainline user of steam-locomotion in America. (Pennsy tried to stay with coal-fired steam-locomotion too.)

Norfolk & Western designed and built its own steam-locomotives. Few railroads did, although Pennsy did also.

But I don’t think Pennsy was doing as good a job.

Norfolk & Western was building steam-locomotives good for its operating profile, which was hilly. Accessing the Pocahontas coalfield meant operating into the Appalachians.

N&W also had a long grade over Blue Ridge Mountain.

The center of Norfolk & Western locomotive design and construction was its locomotive shops in Roanoke.

Roanoke became a railroad-town. Even now the railroad passes right through it — which is what is depicted here.

The large tan building at left is Norfolk & Western’s headquarters. The white building behind was the Hotel Roanoke, still a very glitzy hotel. It was built by the railroad in 1882, donated to Virginia Tech in 1989, and reopened as a hotel in 1995.

A railroad webcam is in the Hotel Roanoke aimed at the route through town.

Or at least it was. I can’t get it to work (the colored text). Horseshoe Curve had one too, but I think it’s deactivated.

The first two locomotives are Norfolk Southern Heritage-Units. In 2012 Norfolk Southern had 20 of its new locomotives, in two orders, painted schemes of railroads that become part of Norfolk Southern.

The lead locomotive is painted in the colors of Southern Railway, the second in colors of Illinois Terminal. I’ve seen some of the Heritage-Units myself, like the Pennsy Heritage-Unit, and Nickel Plate Heritage-Unit, among others.

The Heritage-Units attract a lot of attention. My brother from northern DE works at an oil-refinery that receives crude-oil from Norfolk Southern.

He explains how he has to tell refinery security why so many are around to photograph a train. Like, it has a Heritage-Unit on the point.

Roanoke is no longer the glorious railroad town it was during Norfolk & Western. Even the Hotel Roanoke changed hands.

But it’s still a shop-town, maintaining locomotives for Norfolk Southern. It also celebrates its railroad heritage.

And the Pocahontas coalfields are still pumping out rivers of coal.

But I wonder looking at this picture. The train is westbound, and appears to be a loaded coal-train — although it may be empty.

Coal is not high-dollar traffic like stacked containers. But Norfolk & Western moved so much it became the most successful American railroad.

1970 W-30 4-4-2 Olds. (Photo by Peter Harholdt©.)

—The March 2015 entry in my Motorbooks Musclecar calendar is a 1970 W-30 4-4-2 Oldsmobile.

4-4-2 wasn’t enough, much as G-T-O became not enough.

The first 4-4-2s were the 1964 model, an option on the F-85 and Cutlass. 4-4-2 stood for four-barrel carburetor, four-speed floorshift, and dual exhausts.

But everyone was jumping in the musclecar market, including Ford and Chrysler. There had to be faster and more powerful versions of the 4-4-2 and G-T-O.

They were the W-30 and “Judge” versions.

Supposedly a 4-4-2 handled better than a G-T-O, which would slide you off the road if pressed. Supposedly a 4-4-2 wouldn’t. So said Car & Driver magazine, but one has to remember Car & Driver was mainly selling advertising-space.

A W-30 had a gigantic hot-rodded 455 cubic-inch engine, as did the Stage One GSX Buick. Chevy had a 454, and I think Pontiac was 455 in its Judge.

Such a motor is overkill, but fun in a straight line. That is, if you could get those rear tires to hook up.

Bend such a car into a corner, and it would plow with all that motor-weight on its front tires.

A humble two-liter BMW 2002 could beat it over a bumpy curvy rural road. 455 cubic-inches is almost 7.5 liters!

That 2002 would be sent packing on an expressway.

The W-30 4-4-2 generated gobs of torque. Only the Stage One GSX Buick generated more.

Both could smoke their drive-tires, but I think the 4-4-2 looks better. Just not as good as the first G-T-O, the ’64.

|

| 1964; the first G-T-O. (Photo by Peter Harholdt©.) |

The concept sold many cars; young macho dreamers hot to beat the other guy.

But a friend told me he had a G-T-O, and it was punishing. He poked through turns lest it hurl him into the trees.

U-boat. (Photo by Ray Mueller.)

U-boat. (Photo by Ray Mueller.)—The March 2015 entry in my All-Pennsy color calendar is two Pennsy U-25s heading a freight toward Enola (“aye-NOLE-uh;” as in “hey”) yard near Harrisburg.

The U series, which stood for “utility,” was General-Electric’s first entry into the railroad road-power locomotive market. Railfans called ‘em “U-boats.”

As such they were serious competition to General-Motors’ EMD locomotives, especially its four-axle Geep series.

EMD locomotive design was not as advanced as the U-boats.

Until the U-boat, EMD pretty much dominated the railroad locomotive market.

There was Alco (American Locomotive Company) of Schenectady.

But Alco was using GE traction-motors, and pretty much failed after GE cut them off — which was when the U-boat was introduced.

General-Electric has gone on to pretty much dominate the locomotive market. The U-boats were replaced with Dash-8 and Dash-9 road power.

EMD is no longer part of General Motors; it was divested during the GM bankruptcy and bought by Caterpillar.

But EMD continues to build competitive road-power, and hasn’t been skonked by GE.

EMD engineered a four-cycle diesel prime-mover, but continues to build its two-cycle diesels; mainly because two-cycles can more easily comply with emission regulations.

The first EMD diesel-locomotives, long ago, were two-cycle, and have remained pretty much the same since then, although they were turbocharged.

My calendar says this train is from south Jersey, which means it probably started in Pavonia Yard (“puh-VONE-eee-uh;” as in “own”) outside Camden.

The train is in PA, probably coming off Delair Bridge (“duh-LARE”) over the Delaware River — in northern Philadelphia.

I could have run the next picture ahead of this one. I have steam-locomotion fans.

But I think the U-boat is important, plus it’s a better photograph.

Step aside. (Photo courtesy Joe Suo Collection©.)

—The March 2015 entry of my Audio-Visual Designs black-and-white All-Pennsy Calendar is a K4 Pacific (4-6-2) powered passenger-train passing a waiting westbound merchandise freight powered by an M-1a Mountain (4-8-2).

|

| The crew of a freight-train awaits a passenger-train. (Photo courtesy Joe Suo Collection©.) |

In that picture the crew is looking for the approaching passenger-train.

The K4 Pacific was Pennsy’s standard passenger locomotive for years. It’s beautiful, but it’s an old design, from the teens.

Pennsy never developed a more up-to-date steam passenger locomotive until after WWII.

They were pouring investment into electrification. Plus, if one K4 wasn’t enough, they would doublehead K4s. That’s two locomotive crews per passenger-train; you can’t multiple steam-locomotives like diesels.

And Pennsy could afford multiple crewing. Other railroads were more financially strapped than Pennsy.

Which is why other railroads developed multiple-drivered articulateds — one boiler pushing two driver-sets. Pennsy could afford doubleheading.

|

| Pennsy’s Broadway Limited (left) and New York Central’s 20th Century Limited (right) race out of Chicago. |

If it was one K4, New York Central could win. Central’s Hudson was more advanced. But Pennsy would doublehead K4s to handle the train-weight. In which case Pennsy might win.

The steam-locomotive Pennsy developed to replace the K4 was the T1, a beautiful engine styled by Raymond Loewy.

|

| Loewy’s T1. |

It wasn’t articulated. Those driver-sets were on a common frame, which meant it had a long driver wheelbase, not good for negotiating curved track.

And the front driver-set was more lightly loaded than the rear driver-set, which gave it a tendency to break traction and slip.

Suppose a T1 with a passenger-train was cruising at 100 mph, and the front driver-set started wildly slipping.

The engineer had to back off the throttle, And that’s to both driver-sets.

T1s were also smoky.

K4s lasted until the end of steam on Pennsy, which was 1957, and what we have here.

Only two K4s were saved, #1361 and #3750. 3750 is on static display at Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania in Strasburg, PA. 1361 is disassembled in Altoona. It was on display for years at Horseshoe Curve, then operated, then was being repaired for continued operation. That failed. It’s now being only restored for display.

By the time this picture was taken, diesels had already made inroads, and were probably pulling premier passenger-trains.

My guess is this K4 passenger-train is an all-stops local. Stop at every podunk town along the railroad, whereas a premier train might make only 2-to-4 stops.

Pennsy developed a K5, a much bigger K4 with the boiler of an I1 Decapod (2-10-0). But only two were built.

That M1 at 4-8-2 could also be said to be a K4 successor, but it was more a dual-purpose engine. A K4 had 80-inch drivers; the M1 was 72. The M1 ended up mainly hauling freight.

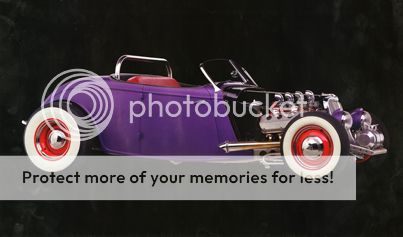

Strange. (Photo by Scott Williamson.)

—Featured in my Oxman Hotrod Calendar is a very strange car, more an engineering triumph than a hotrod.

The car is a ’33 Ford roadster with a 354 cubic-inch Chrysler Hemi (“HEM-eee;” not “HE-mee”) engine.

But its radiator is in the rear, not encased in that grille.

|

| Note see-through grille. (Photo by Scott Williamson.) |

At least the car looks like a hotrod.

I’m also a bit put off by that slanted two-piece windshield. It’s from a ’36 Auburn, not the Duvall two-piece.

I prefer the flat one-piece windshield, stock on a ’33 Ford.

I wonder if this car is drivable. It probably is, if its owner put all that effort into making that rear-mounted radiator work.

And if it’s drivable you hope it doesn’t rain. No top, and no windshield-wipers.

The carburetors also don’t have filtration. That motor will be ingesting pebbles and bugs.

1970 SS 396 Chevelle.

—The March entry of my Jim LePore Musclecar calendar is a 1970 396 SS Chevelle.

To me one of the best-looking musclecars ever built.

My brother-in-Boston has a 1971 454 SS Chevelle, and it has only two headlights.

Compared to 1970 with its four headlights he prefers the two-headlight 1971.

|

| Not my brother’s car, but similar (same color). (Photo by BobbaLew.) |

Everything was shaking: the hood, the fenders, the entire front-end. It was pounding the ground at idle.

It had no choke. You started it by goosing the accelerator-pumps.

Then you let it warm up.

It was automatic transmission, but you had to keep the revs up lest you soot the plugs.

I backed out a driveway, and almost killed it. Were it not for being able to rev between gears I would have.

My Ford Escape is nowhere near as fast, but much more pleasant to drive. I don’t have to pay heed to it; all I do is drive.

And of course my Escape gets much better mileage, about 22-24 instead of 5. And it uses 87 gas, not as high as I can get.

When my brother and I took out the Chevelle he was going to buy racing-gas. $100 just to fill his 20-gallon tank.

My brother’s car is only an LS-5, not Chevrolet’s LS-6 megamotor. But it’s hot-rodded. It probably generates more power than an LS-6. That choke-less carburetor is not a Chevrolet part.

An SS Chevelle is a collector-piece. My brother calls his 454 a museum-piece.

This car is only a 396. It’s a Big-Block, but I think 454 cubic-inch versions were available.

But it still looks pretty good. Especially the fact it’s red, but that makes it cop-bait.

One night about 3 a.m. when my wife and I lived in Rochester, it was summer, and we had our bedroom window open — since our house wasn’t air-conditioned.

Our house was on a busy city-street, and our bedroom faced the street.

All-of-a-sudden BAR-OOOM! Unmuffled musclecars roared by our house. WIDE-OPEN THROTTLE; WOUND TO THE MOON! Woke us right up!

Later I heard them up on the expressway, reaching for 140-150 mph.

Ya don’t find cars like that any more.

Labels: Monthly Calendar Report