Monthly Calendar-Report for April 2014

I almost considered walking away this time; I had only done my own calendar, and had all the rest to do — it was March 26th.

But I know I have people who look forward to this, and it looked like I could get it done quickly.)

The “Queen of the West End.” (Photo by Jack Hughes.)

—The April 2014 entry of my own calendar is restored steam-locomotive Nickel Plate 765, the finest restored steam-locomotive I have ever seen.

The photograph was taken by Jack Hughes, my brother from Boston.

I had to move heaven-and-earth to get him to see this thing back in 1993.

“Jack, you gotta see this engine!”

“How do I find it, Bobby?”

“Just look for the smoke,” I exclaimed.

I suppose you could say Norfolk & Western J #611 (4-8-4), is even better, but 611 is retired and no longer in service.

I rode behind 611. It has roller-bearings in everything, even the siderods.

But 611 was restricted to 45 mph after derailment of its following train.

45 mph is hardly what 611 was capable of, and thankfully I rode it before the derailment.

We were cruising at 80 mph!

To me comparing 611 to 765 is like comparing a Big-Block Chevy to the SmallBlock Chevy. Both can be extraordinarily powerful. 611 is the Big-Block, 765 the SmallBlock.

765 may also be limited to 45 mph on Norfolk Southern. 611 was operating on Norfolk Southern, a merger of Norfolk & Western and Southern Railway.

But 765 was restored to what it did years ago, boom-and-zoom.

I rode behind 765 years ago, and we cruised at 70+ mph.

I will never forget it! That’s goin’ to my grave.

We were pulling a 33-car fall foliage excursion through New River Gorge on Chesapeake & Ohio through WV.

C&O gave us the railroad, all green signals.

Throttle-to-the-roof! We clocked it.

We passed a stopped coal-train in a siding: zoom-zoom-zoom-zoom! Perhaps three cars per second.

A gondola-car was in front of our car with a generator to power our cars.

That gondola was rockin’-and-rollin’, twisting this-way-and-that.

I doubt that gondola had ever gone that fast.

You don’t have to pussyfoot 765.

The restoration was by Fort Wayne Railroad Historical Society, a private group, not a railroad.

Yet it was restored to do what Nickel Plate had done, move fast-freight into Buffalo (NY) thereby competing with New York Central, actually Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway at first, which had a monopoly until Nickel Plate.

Nickel Plate is actually New York, Chicago & St. Louis.

Legend has it a New York Central executive declared it was nickel-plated because it was so competitive.

But actually it was a newspaper in Norwalk, Ohio. People were desperate to get NY,C&StL to route through their town, and would send parties to lobby the proposed railroad, which they declared to be nickel-plated. When a railroad survey-team arrived in Norwalk. the newspaper declared the railroad to be “nickel-plated.”

But NY,C&StL went through Bellevue, instead.

The railroad renamed itself “Nickel Plate.” Norfolk & Western merged Nickel Plate in 1964.

765 is a Lima (“LYE-muh;” not “LEE-muh;” as in “lima-bean”) SuperPower 2-8-4 Berkshire, named after the mountains in western Massachusetts that wheel-arrangement was designed to conquer.

“SuperPower” was Lima Locomotive’s attempt to sell standard side-rod steam-locomotives by improving locomotive performance.

Previously Lima had constructed Shay logging locomotives, which weren’t side-rod.

The main goal was to improve steam-generation at speed. A SuperPower locomotive wouldn’t run out of steam at speed.

They had a gigantic firebox grate and boiler.

The idea was to keep up with steam-demand at speed.

SuperPower was perfect for Nickel Plate. They needed engines that could boom-and-zoom. Dragging up hills wasn’t required.

Nickel Plate bought a slew of SuperPower Berkshires.

My brother and I went to Altoona (PA) to see 765.

765 would pull Employee-Appreciation excursions up The Hill and around Horseshoe Curve.

I needn’t explain Horseshoe Curve. I’ve done it may times in this blog. I’ll just say it’s the BEST railfan-spot I’ve ever been to.

I have a slew of 765 photographs my brother-and-I took; I suppose I should run as many as I can.

I even considered an all-765 calendar, but I didn’t have enough calendar-quality pictures. Many are repeats.

|

| Nickel Plate 765, the BEST restored steam-locomotive of all. (Photo by Bobbalew.) |

765 came out to back up and go get its train.

That’s what’s in the calendar-picture.

765 has an auxiliary water-car that was used on 611 excursions. It lessens having to stop and fill the tender from a fire-hydrant. Water-towers are no longer along the railroad.

765 wouldn’t use much water just climbing The Hill. And coming back down it’s not working steam.

765 would climb The Hill in the lead, with Norfolk Southern Pennsy Heritage-Unit #8102 pushing.

Coming back down was just the reverse of going up, except now 8102 was leading, and 765 was in reverse on the back end.

765 has a GPS transponder. You can get an app for your SmartPhone to tell where it is.

I have since added that app to my iPhone, but my brother installed it there on his Android.

“Here it comes!” my brother shouted. We were on the 24th St. overpass in Altoona over Slope Interlocking.

765’s GPS had it leaving Altoona station.

After shooting we roared up to Gallitzin (“guh-LIT-zin;” as in “get”), the top of The Hill, to snag it coming out of the tunnel atop the mountain.

It burst out of the tunnel, whistle shrieking; a thrill for this old widower.

The shot pictured is actually my second shot — 765 ran two uphill excursions per day. My first shot was obscured by a fan. People had come out from everywhere to see 765.

I didn’t have much location-selection, not what I usually have in this calendar.

Just up-and-back four times, twice per day (Saturday and Sunday). That passes maybe three locations per trip.

And many of those locations there was not enough time to get to, or from.

I had to make do with “cheat-shots.” 765 looks like it’s leading, but actually it’s in reverse, the train backing down.

My third picture is a “cheat-shot.” 8102, in the distance, is leading going away.

765’s firebox would trip the hot-wheel detector at milepost 238.2.

It’s the first I’ve heard that detector go ballistic.

“Emergency, emergency!” it screamed. “Stop your train!”

Knowing many railfans follow this here blog, and -a) steam-locomotives excite many railfans, and -b) Nickel Plate 765 is the BEST restored steam-locomotive I have ever seen.......

Herewith:

Off we go, to the station — train in tow. (Photo by BobbaLew.)

The best there is. (765 crests The Hill.) (Photo by Jack Hughes.)

My cheat-shot; the train is actually backing. 8102 is pulling at the other end. (Photo by BobbaLew.)

Another cheat-shot. (Photo by BobbaLew.)

In profile — “The Queen of the West End.” (Photo by Jack Hughes.)

“The Hill” is of course the railroad-grade over Allegheny mountain; what was a barrier to trade across PA in the early 1800s. “The Hill” includes Horseshoe Curve, the trick John Edgar Thomson used to get the Pennsylvania Railroad over Allegheny mountain without steep grades.

The railroad still uses Thomson’s alignment. Horseshoe Curve opened in 1854.

The grade isn’t very steep, only 1.75% on average on the eastern slope. The western slope is easier.

1.75% is 1.75 feet up for every 100 feet forward.

Had it not been for Thomson, Pittsburgh may have gravitated toward the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and Baltimore instead of Philadelphia.

The Pennsylvania Railroad considered Horseshoe Curve a venerable icon.

Pennsy passenger-trains would stop so those therein could view Horseshoe Curve. Horseshoe Curve was on a Pennsy calendar.

It’s now a historical site. A funicular inclined-plane railroad has been built up to the viewing-area, and museum buildings installed.

I have been to many railfan sites, and I still consider Horseshoe Curve to be the best. The trains, and there are many, are right in your face!

Nickel Plate Railroad was very happy with its Lima SuperPower Berkshires.

In fact, Nickel Plate continued to use steam power until 1960; they were one of the final steam holdouts.

And apparently Nickel Plate 765 ended up being one of the railroad’s finest Berkshires; so good they nicknamed it “The Queen of the West End.”

Many Nickel Plate Berkshires were saved, including 765. At first 765 was renumbered to 767, and displayed in Fort Wayne, IN, in honor of the elevation of Nickel Plate trackage through the city.

Volunteers set about restoring the locomotive, changing it back to 765.

One of the restorers was Rich Melvin, who wanted 765 to be the fantastic engine she once was.

And she is. 765 can boom-and-zoom!

Another group set about restoring another Lima SuperPower Berkshire, Pere Marquette (“pear mar-KETT”) 1225, the Polar Express engine.

But unfortunately 1225 is a joke compared to 765. The two locomotives ran side-by-side in WV, and 765 put 1225 on-the-trailer.

I think 1225 even crippled, sorta. They had to stop; 1225 couldn’t run like 765.

And 765 was pulling a train; 1225 wasn’t.

765 is the BEST there is, and I think we can thank Rich Melvin.

Two Norfolk Southern heritage-units lead a crude-oil train along the Ohio river. (Photo by Roger Durfee.)

—Durfee strikes again!

The April 2014 entry in my Norfolk Southern Employees’ Photography-Contest calendar is by Roger Durfee, a Norfolk Southern conductor.

I always like Durfee’s pictures because he has an appreciation of setting, the landscape the railroad negotiates.

Filling your frame with locomotive is nice, but to me setting is what makes the picture.

Here a long Norfolk Southern crude-oil train is threading old Pennsy trackage next to the Ohio river approaching Pittsburgh.

At least I think it’s Pennsy.

I can think of at least two other Durfee pictures that ran in this calendar. The calendar says he’s been in six times.

I could only find one, his winter shot looking into the rock cut at Cassandra (“kuh-SANN-druh;” as in “Anne”) Railfan Overlook.

|

| Through the cut at Cassandra. (Photo by Roger Durfee.) |

|

| My fall-foliage shot at the overlook. (Photo by Bobbalew.) |

I tried the same photograph years ago as a fall-foliage shot, but it’s not very good. My train was on Track Two; nothing was on Track One.

Durfee’s shot is not fall foliage, but his train was on Track One, which makes it a cheat-shot. The helper-engines on the rear of the train look like they’re pulling the train toward you. But they aren’t.

The train is descending “The Slide,” which gets Track One back to the levels of Two and Three. New Portage tunnel is above the original Pennsy tunnel.

It’s fairly steep, 2.28%; down 2.28 feet for every 100 feet forward.

Until the railroad gets Track One signaled both ways, if it ever does, Track One is always eastbound, and Durfee’s picture, like mine, is looking east.

Anything on Track One is going away.

But I can’t find that Durfee photograph, although I can picture it.

I notice this train is led by Heritage-Units. The lead locomotive is 8025, the Monongahela Heritage-Unit. Trailing is 1074, the Lackawanna Heritage-Unit. Norfolk Southern bought 20 new locomotives and had them painted the schemes of predecessor railroads. 8025 is the colors of Monongahela Railway, and 1074 is Delaware, Lackawanna & Western.

|

| 8102. (Photo by Bobbalew.) |

|

| 8100. (Photo by Roger Durfee©.) |

|

| The Virginian heritage-unit. (Photo by Jack Hughes.) |

|

| The Illinois-Terminal unit. (Photo by Jack Hughes.) |

I’ve seen a few, including 8102 and 8100, Nickel Plate Railroad. I’ve also seen the Virginian and Illinois-Terminal Heritage units.

The Heritage-Units operate just like other Norfolk Southern diesels. You’re as likely to see one as regular Norfolk Southern.

The train is extremely long; it goes back clear out-of-sight.

It’s much longer than the average model-railroad train, which might max out at 30-40 cars.

Model railroads are fun, but can’t be like the real thing.

I see the train is also threading six tracks. (In fact, it looks like a seventh track was removed.)

Six tracks seems extreme, but maybe we’re approaching a yard.

I can’t see Norfolk Southern maintaining a six-track main.

Although so much crude-oil is moving by train any more, rail-capacity is being strained.

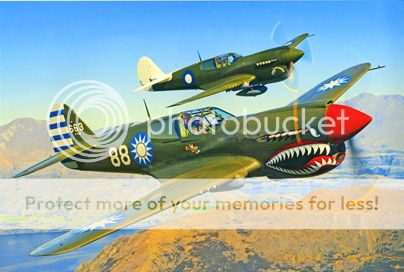

Tiger-shark! (Photo by Philip Makanna©.)

The April 2014 entry of my Ghosts WWII warbirds calendar is two Curtiss P-40 KittyHawks; one painted the shark’s-teeth scheme of General Claire Chenault’s American Volunteer Group (The Flying Tigers) in China. The other airplane, thankfully, lacks that.

I have seen those shark’s-teeth painted on far too many airplanes.

The P-40, with its gigantic radiator-scoop, is the only airplane they work on.

There was a Navy jet during the ‘70s that had a scoop up front that served as an air-intake.

They work on that.

But painting them on a Huey helicopter was a joke.

The stupidest application I’ve seen was on an L-4 Grasshopper reconnaissance plane, essentially a Piper-Cub. A Piper-Cub is hardly lethal, and those shark’s-teeth denote lethality.

It wouldn’t take much to blast a Piper-Cub out of the sky.

Those shark’s-teeth were the trademark of the Flying Tigers, and they appeared on their P-40s.

The P-40 wasn’t an extraordinary airplane. But it was for its time, just before WWII.

P-40s saw combat-duty at the outset of the war.

Better fighter-planes were developed, like the P-51 Mustang.

I’ll let my WWII warbirds site weigh in:

“The P-40 fighter/bomber was the last of the famous ‘Hawk’ line produced by Curtiss Aircraft in the ‘30s and ‘40s.

It was the third-most numerous U.S. fighter of WWII.

An early prototype version of the P-40 was the first American fighter capable of speeds greater than 300 mph.

Design work on the aircraft began in 1937, but numerous experimental versions were tested and refined before the first production version of the P-40, the Model 81, appeared in May 1940.

Early combat operations pointed to the need for more armor and self-sealing fuel tanks, which were included in the P-40B. These improvements came at price: a significant loss of performance due to the extra weight. Further armor additions and fuel tank improvements added even more weight in the P-40C.

Curtiss addressed the airplane’s mounting performance problems with the introduction of the P-40D, which was powered by a more powerful version of the Allison V-1710 engine, and had two additional wing-mounted guns. The engine change resulted in a slightly different external appearance.

Later, two more guns were added in the P-40E, and this version was used with great success (along with their mainstays, the earlier B-models) by General Claire Chenault’s American Volunteer Group (The Flying Tigers) in China.

Some additional models, each with slight improvements in engine power and armament, were the P-40F (with a 1,300 horsepower Rolls-Royce Merlin engine), the P-40G, P-40K, P-40L, P-40M and finally, the P-40N, of which 5,200 were built (more than any other version.)

While it was put to good use and was certainly numerous in most theaters of action in WWII, the P-40’s performance was quickly eclipsed by newer aircraft of the time (for example, the Mustang), and it was not considered one of the great fighters of the war.”

Years ago the local Historical-Aircraft Group in nearby Geneseo (“jen-uh-SEE-oh”) had a P-40.

But I think it had to be crash-landed. Its engine failed returning from a show.

Who knows if that P-40 is back flying. I don’t think the Historical-Aircraft Group has it any more.

That P-40 without the shark’s teeth is a rare bird. I’ve seen far too many P-40s with the shark’s teeth.

Too much of a good thing!

That closest P-40 is painted as a “Flying Tiger,” and has Chinese identification markings.

A 1972 Hurst-Oldsmobile Indy pace-car. (Photo by Peter Harholdt©.)

—The April 2014 entry in my Motorbooks Musclecar calendar is a 1972 Hurst-Olds Indy pace-car convertible.

After 1971, when a Dodge Challenger overshot the track-exit, and plowed into the press-box........

No manufacturer wanted to supply pace-cars to the Indy-500 any more.

So George Hurst, who partnered with Oldsmobile earlier to do the Hurst-Olds, independent of Oldsmobile with it 4-4-2, offered to supply a Hurst-Olds to be Indy pace-car.

So here we have a 1972 Hurst-Olds Indy pace-car.

|

| A Hurst floor-shifter. |

A Hurst shifter could be slammed hard on upshift without damage.

Slam a typical manufacturer four-speed floor-shifter from second to third, and it might go wonky.

A Hurst shifter could take it.

I never liked the Hurst-Olds.

For one thing the intermediate Oldsmobile, on which this car is based, is too big.

That’s true of all musclecars. Detroit’s musclecars are all based on intermediate offerings.

And no way would I drive a car that advertises itself as an “official pace-car.”

I prefer the sleepers, the cars no one would know are musclecars.

I look at this car, and I see “your father’s Oldsmobile.” —Also something I wouldn’t be caught dead in.

N2sa Santa Fe (2-10-2) plods slowly along on the Pennsy main in 1947 across Indiana. (Photo by Tom Harley.)

N2sa Santa Fe (2-10-2) plods slowly along on the Pennsy main in 1947 across Indiana. (Photo by Tom Harley.)—The April 2014 entry of my All-Pennsy color calendar is a Pennsy freight-train, pulled by a 2-10-2 Santa Fe engine, near Schererville, IN.

The N2sa was a Pennsy design, although mainly it was “Lines West,” west of Pittsburgh; the many merged railroads that fed the original Pennsy main in Pittsburgh.

“Lines West” didn’t have the challenges of railroading in PA.

“Lines West” locomotives tended to be more laid back, and like the average locomotive.

|

| The Belpaire firebox on an actual N2sa. |

|

| Pennsy’s Decapod (2-10-0). |

East of Pittsburgh a 10-drivered locomotive was the Decapod (2-10-0), sort of a 10-drivered Consolidation (2-8-0).

All 10-drivered locomotives have the same problem, a heavy side-rod assemblage that pounded the rail as the drive-wheels rotated.

Side-rod weight can be offset with counterweighting, but you can’t do much with a small-drivered freight locomotive.

The rotating side-rod assemblage would also heavily vibrate the locomotive-cab, and its crew. A Decapod could run 55 mph if you could stand it.

These N2sa’s were limited to 35 mph — essentially a drag-engine.

But it’s 1947, and this locomotive is still in revenue service.

Slogging a long drag-freight is what they were good for.

I happened to bring up “Schererville” in my Google satellite-views to check the spelling.

It had photographs of the “Pennsy Greenway.”

Looks like the Pennsylvania Railroad through Schererville was abandoned.

And turned into a walking-trail.

“Schererville” was very flat. It also is awash with railroads, junctions galore.

There were many pictures of grade-crossings. And from them I could do Google “street-views” paralleling railroads.

No doubt that area of Indiana was once awash with railroads headed for Chicago. Many of those railroads were abandoned.

Erie and Pennsy and Baltimore & Ohio and New York Central all had lines into Chicago, plus there were lines east out of Chicago.

Too bad it’s a pickup. (Photo by Scott Williamson.)

—The April 2014 entry of my Oxman Hotrod Calendar is a Model-A pickup extended into a crew-cab.

Except, of course, Ford didn’t build crew-cab pickups back then; not until a half-century later.

The cab had to be stretched 10 inches to make it a crew-cab.

I’ve never been enamored of pickup hotrods.

To me a pickup is a truck. A pickup hotrod is no longer a functional truck.

The roadsters and coupes are more attractive.

|

| The nail-valve head in cross-section. |

|

| TV Tommy Ivo’s four-engine dragster. (That’s Ivo looking at his dragster.) |

The “nail-valve” wasn’t much of a hotrod engine; what makes it a hotrod is its size.

A “nail-valve” V8 couldn’t breathe very well, its valves were too small, reason for the “nail-valve” nickname.

The valves were on one side of a pent-roof combustion-chamber, so had to be small.

The exhaust-passages have to angle all over to get to the outside of the heads — which constricts breathing.

Chrysler’s Hemi (“HEM-eee;” not “HE-mee) was much better, putting the valves on both sides of the pent-roof, but the heads were much heavier.

Buick gave up on the “nail-valve.” It switched to conventional valving.

Yet TV Tommy Ivo built a four-engine dragster back in 1961 that used four Buick “nail-valve” V8s.

At least it’s a steamer. (H. Gerald MacDonald Collection©.)

—And finally.....

The April 2014 entry of my Audio-Visual Designs black-and-white All-Pennsy Calendar is not inspiring.

It’s a Pennsy K-4 Pacific (4-6-2) on a commuter-run that started at Exchange Place in Jersey City, and will end at Bay Head on Central of New Jersey’s New York & Long Branch.

Pennsy got trackage-rights on NY&LB after threatening to build a competing railroad that probably would have put NY&LB out-of-business.

The train is “The Broker,” a famous train.

All commuter railroads serving Manhattan Island are now New Jersey Transit, a government function.

Rail commuter-service became too costly.

Apparently the first cross-Hudson steam ferry-service to Manhattan was from Jersey City, from an area that became “Exchange Place.”

A railroad was built to that ferry, and Pennsy acquired it 1871.

For years Pennsy passenger-trains terminated at “Exchange Place,” until Pennsy tunneled under the Hudson farther north to attain Manhattan directly.

Other railroads terminated in north Jersey across the Hudson from Manhattan Island.

A union railroad-bridge was proposed but never built.

The only railroad to actually attain Manhattan Island from north Jersey was Pennsy. And its tunnels were restrictive. They won’t clear double-deck passenger-cars, and won’t clear freightcars.

Freight still terminated in north Jersey, and still does.

A lot was ferried at first, and some still is. But now most of it is “rubbered” — highway trucks. What used to be shipped in railroad boxcars now ships in intermodal containers, double-stacked in freight-trains, then trailered to their final destinations.

When Pennsy accessed Manhattan directly, “Exchange Place” dwindled. But it lasted a while; it was finally closed as a Pennsy station in 1962.

But it was still in use when this photo was taken in 1956.

And a lot of business was being transacted in Jersey City; so a lot of the passengers on “The Broker” may not have been from Manhattan.

The train is passing through “Hunter” in Newark. Hunter is one of the most impressive railroad facilities Pennsy built.

Hunter is just north of Newark station, and the railroad crosses the Passaic river on an impressive drawbridge.

The Newark station is also a terminus of the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad — now PATH (Port-Authority Trans-Hudson) since 1962.

Hudson & Manhattan was financed by Pennsy; it’s additional tunnels under the Hudson to Manhattan.

But it’s more a rapid-transit, not the railroad Pennsy is in its own tunnels.

In order to terminate at Newark station, Hudson & Manhattan had to build extensive bridging to bridge both Pennsy and the Passaic river.

So Pennsy through Hunter is impressive. Add overhead electrification and it becomes incredible.

Going through Hunter is mind-boggling. Your train negotiates a tunnel of wires and bridgework. (That old Pennsy line is now the Northeast Corridor.)

So here we have “The Broker” doing pretty much the same.

Trains from Exchange Place in Jersey City negotiated Hunter to get to the Pennsy main. —In fact, the line to Exchange Place was once the Pennsy main, and Pennsy’s line to its Hudson-river tunnels looks more a branch; it’s only two tracks.

Exchange Place was also a terminus for PATH. Hudson & Manhattan’s tunnels opened in 1910, and terminated under the World Trade Center, which was destroyed by terrorists in 2001.

In other words. Hudson & Manhattan accessed Manhattan Island farther south than did Pennsy, whose terminal was up at 32nd St.

The coach of a Pennsy Blue-Ribbon passenger-train to New York City is stopped at right.

Labels: Monthly Calendar Report

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home