Stink

“Delaware City” is a tiny town south of Wilmington, DE the refinery is near. —I think it’s at the Delaware river end of the cross-peninsula Chesapeake & Delaware canal.

The Valero gas-station is along our way to Rochester, NY, and since our car was approaching empty, I decided to hit the Valero instead of the place I usually buy gas in West Bloomfield, which the car would have attained, but costs more.

We live in the small rural town of West Bloomfield, southeast of Rochester.

The Valero seems to be in a price-war with a nearby competitor. They both have the lowest price per gallon I’ve seen recently, $3.35.9.

Our West Bloomfield gas-station would want around $3.44. I’ve seen it as high as $3.49.9 at a gas-station I no longer patronize.

The Delaware City refinery opened in 1956 as a “Flying-A” refinery, Tidewater Oil.

It was designed to process so-called “sour crude,” foul-smelling stuff from Venezuela, the opposite of “sweet-crude” from Saudi Arabia, which is easier to refine.

“Sour crude” apparently has sulfur in it, but is cheaper.

My father got a job in that refinery when it opened. He had previously worked in a south Jersey Texaco refinery.

That job was the reason our family moved from south Jersey to northern Delaware in late 1957.

That refinery went on to become various oil-companies, although I think it stayed Tidewater (“Flying-A”) as long as my father worked there.

His job was a step up from his job at Texaco. He became an inspector, semi-management, and retired as management.

My father retired in 1981, and died in 1994 in south Florida of Parkinson’s Disease.

My younger brother Bill still works at that refinery, although it’s had various owners during his employ.

Texaco sold its south Jersey refinery, and purchased the Delaware City refinery.

It’s had other owners since, and a recent owner was Valero.

Valero gave up on the Delaware City refinery not too long ago, and was gonna shut it down.

But somebody else bought it.

I worked at the Delaware City refinery myself after my freshman year at college. But not for Tidewater, or even the permanent contractor they had working for them: Catalytic Construction.

I worked for Myers & Watters (pronounced “Mahz n Wawdzzz;” [as in “ah”], the way my Greek supervisor pronounced it), a painting contractor.

Like all oil-refineries the Delaware City refinery had steel equipment that needed painting: tanks, pipes, and towers/what-not.

My father arranged the job.

He inspected the work of Mahz n Wawdzzz, and was justifiably quite fussy about it.

Like most contractors, Mahz n Wawdzzz was hot to take shortcuts.

My father suggested to that Greek supervisor at Mahz n Wawdzzz a summertime job for me, to help defray my college expenses.

But I wouldn’t be union.

The union would permit me on-site, but at a lower pay-rate.

For Mahz n Wawdzzz it was “you scratch my back, and I’ll scratch yours.”

I had a job, but I don’t think my father was any less fussy.

And Mahz n Wawdzzz loved me. I always showed up on time, and was willing to work.

Our first job was painting a pipeline to the docks.

My job was to sand pipe-bottoms for painting, and the pipes were about a foot or two above the ground. —I used to call it “making love to the pipes.”

Making love to the pipes. (That’s the cat-cracker back there.) (Photo by BobbaLew.)

One time I cleaned caked oil and grease off a leaky pipe junction, a very dirty job. The pipes were massive, about three feet in diameter. —Most of the other pipes were three to eight inches, sometimes a foot.

My second job was to help union-painters painting a large 48-foot high tank.

But that only lasted a week or two. Our rigging slipped and a fellow worker almost fell to the ground; 48 feet.

I was scared after that, but scared even before that.

I was taken off that job and put on job number-three, filling two sandblasters cleaning rust and scale off of four-story steel-encased heater units.

Both guys are sandblasting. (A Hydrodesulfurization heater.) (Photo by BobbaLew.)

Mahz n Wawdzzz had two kinds of employees (three if you included me), Mahz n Wawdzzz employees and union-hall employees, workers hired from the local painter-union hall.

The Mahz n Wawdzzz employees were also union, but permanent Mahz n Wawdzzz employees.

The other guys weren’t.

The pipeline was mostly union-hall employees, and the guys sandblasting were Mahz n Wawdzzz employees.

One of these two blaster guys had an especially trashy mouth.

He’d go ballistic when things went wrong, and start cursing violently.

The other guy was very friendly, and decent.

One Mahz n Wawdzzz employee was a complete weirdo.

His mission was to make me a sinner, since they all knew my father was very religious.

They were somewhat successful, but I had my standards.

I had to come at that weirdo with a broom once.

My coworkers thought that uproariously funny.

“Little Bobby terrorized ‘The Boog.’” (That was his nickname; “Booger.”)

My job at Mahz n Wawdzzz lasted another four summers, even after I graduated college.

But after college the union wanted me to join, and I wasn’t about to — not after four years of college. So I split for Rochester, NY.

Mahz n Wawdzzz was based in northern Philadelphia, and did jobs as far as 125 miles from base.

The Delaware City refinery was left behind, and I did various jobs all over the area.

One job was tending four six-bag blasters in a south Jersey tank-farm.

The blasters used in the Delaware City refinery were only three-bag, pushed by a small 150 cubic-feet-per-minute rented Schramm compressor.

Our four six-bag blasters were pushed by a giant 600 cubic-feet-per-minute compressor. It had a bus-diesel powering it; 8-71 (V8).

Firing it up and engaging it was a consummate thrill: IMMENSE POWAH! (I was operator.)

The tanks were down inside dikes, in case they leaked. Our Greek supervisor’s son almost flipped that giant compressor backing down an access-road to position it. —You would have needed a crane to rescue it.

He didn’t.

The monster had no brakes, and he was towing it with only a half-ton pickup.

The blaster-guys were upset I was reloading so fast. They couldn’t get a complete cigarette smoked.

But Mahz n Wawdzzz loved it.

The blaster-guys were up inside the tank, and here I was outside signaling I was about to turn everything back on.

Never mind that smoking was verbotten, and they were doing so atop a gigantic floating-roof tank full of av-gas.

Heavy with fumes.

I learned about “blueing;” the addition of blue paint to white to make it look heavier. By adding blueing you could make one coat of white paint look like two.

I also drove a company stake-truck full of equipment to the giant Morris steel-mill near Trenton. (Morris at that time.)

Thank goodness I didn’t have to work in there.

What I remember is how grungy it was, and the giant smoking slag-heaps.

It looked like Hell.

Slag was apparently a byproduct of steel production, especially if they were using melted scrap.

Early after my Junior year at college we moved equipment to a 175-foot high golfball water-tower in Baltimore.

A “Golfball” is a giant spheroid standing atop a single leg, and at 175 feet it was frightening.

I couldn’t do it.

After Baltimore, which was only one day, we transferred to another golfball water-tower in Ventnor, NJ, south of Atlantic City, on the Jersey seashore.

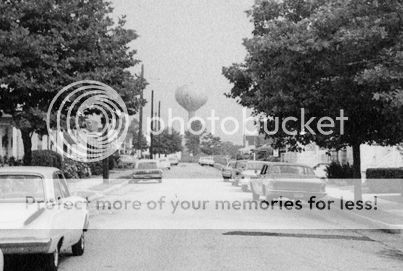

That’s the new Ventnor golfball in the distance. (Photo by BobbaLew.)

It was the best job I ever did at Mahz n Wawdzzz.

At only 125 feet it was much less frightening.

It was also the most fun job we ever did.

It was the seashore, so surroundings were nice.

Again I was tending blaster, but only one three-bag.

On top (accessed through the manhole at right). (Photo by BobbaLew.)

I had two fellow employees. One was the foreman I always worked with, Billy Gardiner, and the other was “Gerald,” fairly pleasant.

Both were Mahz n Wawdzzz employees, and Gardiner was always hot to have me as his helper.

Gardiner painting. (Photo by BobbaLew.)

Gerald always bought lily-white new dress shirts he’d throw out after they got splattered with paint.

He’d also buy a new white Pontiac convertible every year.

This was back in the middle ‘60s, when Pontiac was at its apogee.

Our blasting was superficial, only removing scale from construction, which was like assembling a large kit.

All the steel panels were pre-formed. All you had to do was weld it all together. I suppose a large crane hoisted everything into position.

Hardest for us was painting inside the tank. Gardiner, who did the painting, had an air supply. Gerald and I, the helpers, didn’t.

The paint-fumes made us drunk.

Outside was a challenge too.

Gardiner was the painter, and sprayed.

At least half of what he sprayed blew away.

Our rigging was also challenging, since you have to paint the underside of the golfball.

The painting was done with an air-powered spider, suspended from a quarter-inch steel cable.

The spider had to ride another cable to get close to the tank’s underside.

This was where Gardiner’s experience applied; getting it all to work.

We also had to replace the quarter-inch cable. It started stretching once, and Gardiner was afraid it would fall. —That’s 75 feet above the ground.

|

| Photo by BobbaLew. |

| “Get back! Get back! This thing may fall. The cable is stretching!” —Billy is riding the spider. |

I worked plenty of oil-refineries, but the Delaware City refinery had a distinct smell.

My thought was it was the “sour crude.”

And for some reason the nearby Valero station smells like that.

I wonder if it’s still pumping gas processed by that Delaware City refinery?

• A “floating-roof tank” is just that; its roof floats atop the tank’s contents instead of being solidly-mounted to the tank-sides.

• “Av-gas” is aviation-gasoline, very high octane at that time.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home